Seeing the routes that shaped the Atlantic world

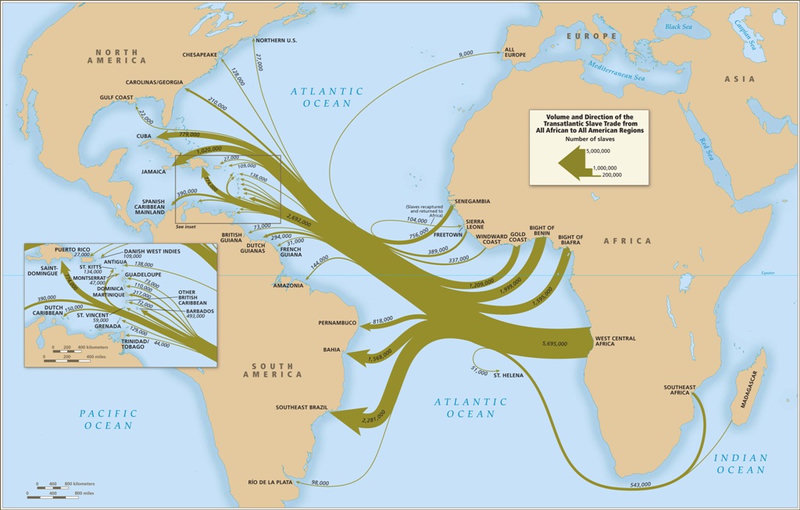

When I first encountered the "Volume and Direction of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade" map in Eltis and Richardson's Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, it stopped me in my tracks.

Here was the entire geography of the slave trade rendered in a single image — thick arrows sweeping across the Atlantic from Africa to the Americas, their widths proportional to the millions of people forced along each route. I could see that Brazil dwarfed every other destination. I could see the Caribbean's enormous share. I could see that North America, for all the attention it receives, was a relatively small piece of the whole. The map conveyed the scale of the trade in a way that tables of numbers never could.

But the more I studied it, the more I wanted to ask questions it couldn't answer. Which parts of Africa supplied enslaved people to which destinations? How did those patterns shift across centuries? What happened when I selected just Jamaica, or just Cuba, or just the Chesapeake? A static map — even a brilliant one — can't do that. You can't filter it. You can't zoom in. You can't watch the routes evolve over time.

That gap is what inspired this interactive version.

What the Map Shows

The visualization renders flow lines from nine African embarkation regions to destinations across the Americas and Europe. Each stem represents the route from one African source region to a selected destination, with thickness proportional to the volume of people transported on that route. The stems converge into a trunk that points to the destination.

The map draws on the same voyage-level data compiled by the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database project, covering both the transatlantic trade and the lesser-known inter-American trade — the redistribution of enslaved people between ports in the Americas after their initial Atlantic crossing.

Selecting a Caribbean destination like Jamaica or Saint-Domingue reveals that the Bight of Benin, the Gold Coast, and West Central Africa were dominant source regions. Selecting Bahia or Rio de Janeiro shifts the pattern dramatically toward West Central Africa and Southeast Africa — reflecting the Portuguese trade networks that connected Angola and Mozambique to Brazil. Using the time slider to compare early periods against later ones shows how trade routes evolved: the British abolition in 1807 redirected traffic; the expansion of sugar cultivation in Cuba drove a surge of voyages to Havana even as other routes contracted.

And the scale disparities become immediately legible. Brazil received roughly 5.5 million enslaved Africans — more than any other region in the Americas — yet this fact is often underappreciated relative to the attention given to the trade into North America, which received approximately 400,000.

Routes and the Sea

The flow lines on the map are not arbitrary curves. They follow plausible maritime corridors shaped by the Atlantic wind and current systems that governed sailing routes during the age of sail. Ships departing from Senegambia or Sierra Leone bound for the Caribbean rode the northeast trade winds on a southwesterly arc. Ships from West Central Africa bound for Brazil took the shorter but still perilous route across the South Atlantic, aided by the south equatorial current. European-bound ships followed the westerlies northeastward.

These routes mattered enormously. Voyage duration affected mortality rates. Ships from Southeast Africa to the Caribbean faced the longest crossings — sometimes exceeding three months — with correspondingly higher death tolls. The geography of the trade was inseparable from its human cost.

What the Database Cannot Capture

As I dug deeper into the data, I kept running into the same limitation. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database documents voyages across the ocean. It does not — and cannot — capture what happened to enslaved people once they arrived in the Americas.

It does not record:

- Domestic sales between slaveholders within a state or territory

- Sheriff's seizures and court-ordered repossessions of enslaved people as property

- Notarial acts of purchase and sale executed in cities like New Orleans, Charleston, and Richmond

- Inheritance transfers, where enslaved people passed from one generation of slaveholders to the next

- The internal forced migration of roughly one million enslaved people from the Upper South to the Deep South between 1790 and 1860

These transactions — smaller in scale than the ocean crossings, but no less devastating to the people caught in them — generated their own paper trail: court petitions, bills of sale, ship manifests for the coastwise trade, notarial records. They are preserved in archives across the former slaveholding states and territories.

I found three such documents in the records of New Orleans. They tell the story of Eulalie Bayeron, a free woman of color who bought, lost, and sold enslaved people between 1807 and 1827. What struck me about these documents is how ordinary they are — routine legal paperwork that treated human beings as transferable property. That ordinariness is what makes them so devastating.

Voices in the Archive: New Orleans, 1807–1827

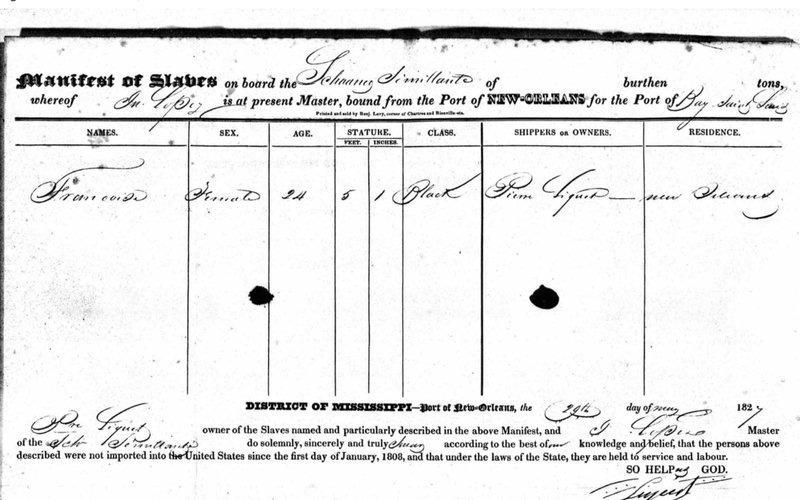

The Ship Manifest

This printed form documents the coastwise domestic slave trade — the movement of enslaved people by ship between American ports. A single entry records Francoise, a 24-year-old Black woman, five feet and one inch tall, shipped by Pierre Liquet of New Orleans aboard the schooner Sémillante, master Jn. Lopez, to Bay Saint Louis, Mississippi.

The manifest's most revealing feature is the oath at the bottom. The shipper and the ship's master swear

solemnly, sincerely and truly ... according to the best of our knowledge and belief, that the persons above described were not imported into the United States since the first day of January, 1808, and that under the laws of the State, they are held to service and labour.

This is the 1808 oath — the legal mechanism by which the domestic coastwise trade distinguished itself from the now-illegal trans-Atlantic importation.[4] The form itself is a kind of legal fiction: it certifies the legality of an inherently brutal commerce by framing it as a question of importation dates rather than human rights. Francoise was not "imported" — she was already enslaved, already within the borders, and therefore could be legally shipped like cargo.

Documents like this one — and there were tens of thousands — do not appear in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Francoise's forced journey from New Orleans to Bay Saint Louis is invisible to the map above.

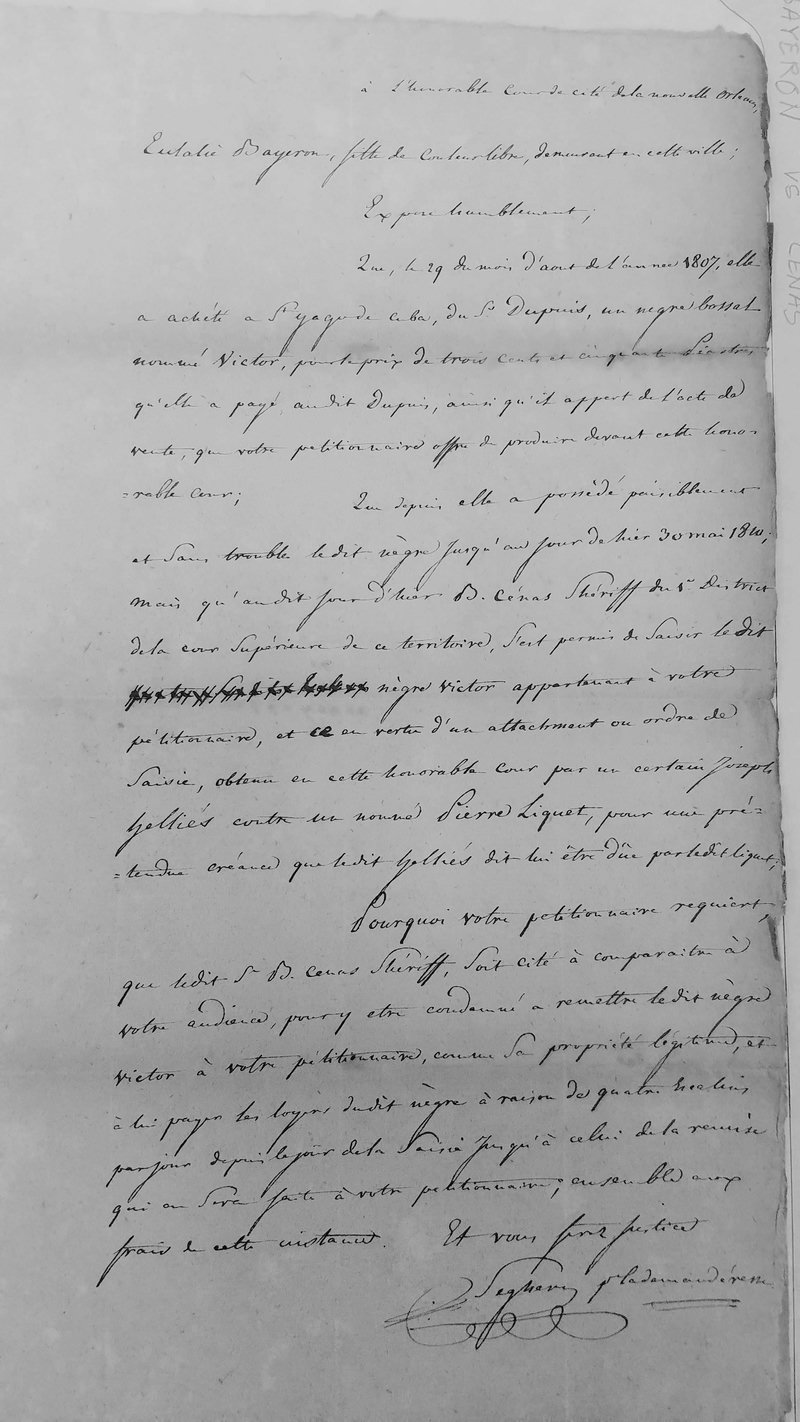

Eulalie's Petition (1810)

Around May 31, 1810, Eulalie Bayeron — identified in the document as a fille de couleur libre, a free daughter of color — filed a petition with the New Orleans city court. She reported that on August 29, 1807, she had purchased an enslaved man named Victor in Santiago de Cuba (S[ain]t Yague de Cuba) from a man named Dupuis for 350 piastres. Victor is described as a nègre bossal — a term derived from the Spanish bozal, meaning a person recently arrived from Africa who had not yet been creolized into the colonial culture.[5]

Eulalie states that she possessed Victor "peacefully and without trouble" until the day before the petition — May 30, 1810 — when Sheriff B. Cénas of the 1st District of the Superior Court seized Victor. The seizure was not for any debt of Eulalie's. It was executed under an attachement (writ of attachment) obtained by a man named Joseph Gelliés against Pierre Liquet, for a debt Gelliés claimed Liquet owed him.

Victor — a human being — was seized as attachable property to satisfy someone else's debt.

Eulalie petitions the court to order the sheriff to return Victor as her "legitimate property," to pay her four escalins per day for Victor's labor from the date of seizure until his return, and to cover all court costs. The petition is signed by Seghers on her behalf.

À l'honorable cour de cité de la Nouvelle Orléans

Eulalie Bayeron, fille de couleur libre, demeurant en cette ville;

Expose humblement;

Que, le 29 du mois d'août de l'année 1807, elle a acheté à S[ain]t Yague de Cuba, du S[ieu]r Dupuis, un nègre bossal nommé Victor, pour le prix de trois cents et cinquante Piastres, qu'elle a payé, au dit Dupuis, ainsi qu'il appert de l'acte de vente, que votre pétitionnaire offre de produire devant cette honorable cour;

Que depuis elle a possédé paisiblement et sans trouble le dit nègre jusqu'au jour de hier 30 mai 1810; mais qu'au dit jour d'hier B. Cénas, Shériff du 1er District de la cour Supérieure de ce territoire, s'est permis de saisir le dit nègre Victor appartenant à votre pétitionnaire, et ce en vertu d'un attachement ou ordre de saisie, obtenu en cette honorable cour par un certain Joseph Gelliés contre un nommé Pierre Liquet, pour une prétendue créance que le dit Gelliés dit lui être dûe par le dit Liquet.

Pourquoi votre pétitionnaire requiert, que le dit S[ieu]r B. Cénas Shériff, soit cité à comparaître à votre audience, pour y être condamné à remettre le dit nègre Victor à votre pétitionnaire, comme sa propriété légitime, et à lui payer les loyers du dit nègre à raison de quatre escalins par jour depuis le jour de la saisie jusqu'à celui de la remise qui en sera faite à votre pétitionnaire, ensemble aux frais de cette instance.

Et vous ferez justice.

Seghers p[ou]r la demanderesse

To the Honorable City Court of New Orleans

Eulalie Bayeron, free girl [or daughter] of color, residing in this city;

Humbly states;

That, on the 29th of the month of August of the year 1807, she purchased at Santiago de Cuba [S(ain)t Yague de Cuba], from the Sieur Dupuis, a bozal negro named Victor, for the price of three hundred and fifty Piastres, which she paid to the said Dupuis, as appears from the act of sale, which your petitioner offers to produce before this honorable court;

That since then she has possessed the said negro peacefully and without trouble until yesterday, the 30th of May 1810; but that on said yesterday, B. Cénas, Sheriff of the 1st District of the Superior Court of this territory, took it upon himself to seize the said negro Victor belonging to your petitioner, and this by virtue of an attachment or order of seizure, obtained in this honorable court by a certain Joseph Gelliés against one named Pierre Liquet, for an alleged debt that the said Gelliés claims is owed to him by the said Liquet.

Wherefore your petitioner requests that the said Sieur B. Cénas, Sheriff, be summoned to appear before your court, there to be condemned to return the said negro Victor to your petitioner, as her legitimate property, and to pay her the hire of the said negro at the rate of four escalins per day from the day of the seizure until the day of the return that shall be made to your petitioner, together with the costs of this proceeding.

And you shall do justice.

Seghers, for the plaintiff

Several dimensions of this document deserve attention.

Free people of color as slaveholders. Eulalie occupied a distinct social stratum in Louisiana — the gens de couleur libres, free people of color who existed in a legal and social space between enslaved Black people and white colonists. Under French, then Spanish, then American law, some free people of color accumulated property, including enslaved people. Eulalie's petition is not unusual for its time; it is part of a well-documented pattern in which the institution of slavery was maintained not solely by white slaveholders but by a broader system in which property rights in human beings were available to anyone with the means to purchase them.[6]

The Santiago de Cuba connection. Victor was purchased in Santiago de Cuba in 1807, one year before the American ban on slave importation took effect. Santiago de Cuba was a major hub for the Caribbean slave trade — the TASTDB records 56 voyages arriving there, carrying an estimated 13,367 enslaved people, predominantly under Spanish and French flags.[7] As a bozal, Victor had likely been brought to Cuba from Africa on one such voyage before Eulalie purchased him there and brought him to New Orleans.

Repossession. The legal mechanism at work here is chilling in its ordinariness. Pierre Liquet owed money to Joseph Gelliés. Gelliés obtained a court order — an attachement — to seize Liquet's property. But it was not Liquet's property that was seized; it was Eulalie's. The sheriff took Victor from Eulalie because someone else's creditor believed that someone else owed him money. A human being was treated as an asset that could be attached, seized, and transferred to satisfy a debt he had no part in.

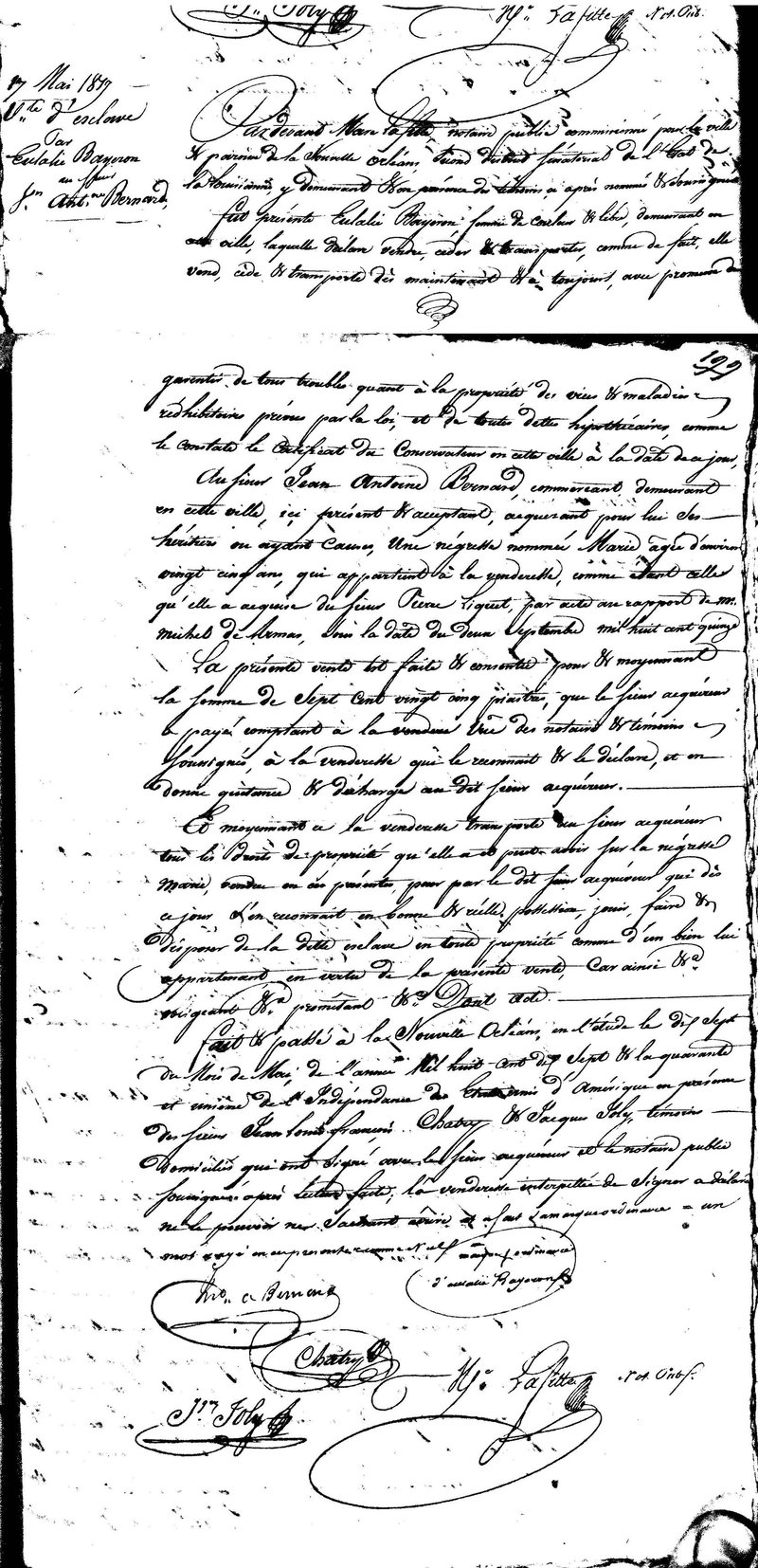

The Sale of Marie (1817)

Seven years after the petition for Victor, Eulalie appears again in the notarial records — this time as a seller. On May 17, 1817, before a New Orleans notary, Eulalie Bayeron sold an enslaved woman named Marie, described as a négrette aged approximately twenty-five years, to Jean Antoine Bernard, a commerçant (merchant) residing in the city, for 725 piastres paid in cash.[8]

The notarial act specifies that Marie had been acquired by Eulalie from Pierre Liquet — the same Pierre Liquet whose debts led to Victor's seizure — by an act before the notary Michel de Armas on September 2, 1815.

...Au sieur Jean Antoine Bernard, commerçant demeurant en cette ville, ici présent & acceptant, acquérant pour lui ses héritiers ou ayants causes, une négrette nommée Marie, âgée d'environ vingt cinq ans, qui appartient à la venderesse, comme étant celle qu'elle a acquise du sieur Pierre Liquet, par acte au rapport de M[aît]re Michel de Armas, sous la date du deux Septembre mil huit cent quinze.

La présente vente est faite & consentie pour & moyennant la somme de sept cent vingt cinq piastres, que le sieur acquéreur a payé comptant à la venderesse...

...To the sieur Jean Antoine Bernard, merchant residing in this city, here present and accepting, acquiring for himself, his heirs, or assigns, a young negress named Marie, aged approximately twenty-five years, who belongs to the seller, being the one she acquired from the sieur Pierre Liquet, by act before Maître Michel de Armas, under the date of the second of September, one thousand eight hundred fifteen [September 2, 1815].

The present sale is made and agreed upon for and in consideration of the sum of seven hundred twenty-five piastres, which the said buyer has paid in cash to the seller...

The Pierre Liquet thread. Liquet connects all three documents across twenty years. In 1810, Liquet's debts to Joseph Gelliés led to the seizure of Victor. Eulalie acquired Marie from Liquet in 1815. By 1817, Eulalie was selling Marie — perhaps to raise capital, perhaps because she needed to, perhaps for reasons the archive does not reveal. And in 1827, Liquet himself appears on the ship manifest as the owner shipping Francoise to Bay Saint Louis. What is clear is that the lives of enslaved people were entangled in webs of debt, obligation, and commerce that extended far beyond any single transaction.

The commodification of Marie. The notarial language is precise and cold: Marie is sold with a warranty (garantie), as one would sell a house or a horse. The act specifies her age, her provenance, the chain of ownership. She is, in the eyes of the law, a piece of property being transferred between parties for a stated price. The notary records the sale; the witnesses sign; the piastres change hands. Marie's own experience of this moment — her fear, her grief, her rage, her resignation — is not part of the record.

The Domestic Slave Trade

The three documents above represent a fraction of a vast archive. Between 1790 and 1860, approximately one million enslaved people were forcibly moved from the Upper South (Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky) to the Deep South (Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama) through the domestic slave trade — a migration scholars have called the "Second Middle Passage."[9]

New Orleans was the largest slave market in the antebellum United States. Between the 1808 federal ban on importation and the Civil War, the city's slave pens, auction houses, and notarial offices processed tens of thousands of sales. None of these domestic transactions appear in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.

The federal ban on slave importation, effective January 1, 1808, did not end the slave trade. It transformed it.

Trans-Atlantic smuggling continued. The TASTDB records 8,459 voyages after 1808, carrying an estimated 2.8 million people. Most of these voyages were bound for Brazil and Cuba, where the trade remained legal longer, but some illegally supplied the American South as well.

The domestic trade expanded. With legal importation cut off, the price of enslaved people in the Deep South rose sharply. Slaveholders in Virginia and Maryland found it profitable to sell "surplus" enslaved people to the cotton and sugar regions. This domestic trade — conducted overland in coffles, by ship along the coast, and through urban slave markets — became one of the largest forced migrations in American history.

The legal infrastructure adapted. Documents like the ship manifest above, with its 1808 oath, represent the legal machinery that enabled the domestic trade to operate openly. The oath was a bureaucratic checkpoint — a moment where the state acknowledged that the trade in human beings required at least the appearance of legal regulation.

The map above tells one story — the oceanic story, the Middle Passage, the ships and the ports and the numbers. The documents tell another: the story of what happened after arrival, in the courts and notarial offices and sheriff's departments of the slaveholding South. Both stories are necessary. Neither is complete without the other.

Primary Sources

Full transcriptions and translations are available on the notes page.

Explore the Full Map

The embedded map above provides the core experience, but the full-page version offers more space for exploring the data, especially on smaller screens.

We welcome feedback and contributions. The source code for the visualization is available on GitHub. If you have corrections, suggestions, or want to contribute to SlaveCodes.org more broadly, please see our contribution guidelines.

References

-

Eltis, David, and David Richardson. Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Yale University Press, 2010.

-

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. slavevoyages.org.

[4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]